Hey friends! As promised, here’s the next installment of my examination of David Epstein’s Range, specifically relating it to what we’re trying to do as musicians. I’m dividing it up by chapter to keep things clear. Before I get underway, I thought I’d share some scenes from the epic snowstorm this part of the world has been dealing with the last few days, along with one particularly wild sunset I encountered on the way back from my first tap lesson.

Range

1. The Cult of the Head Start

This chapter, which I covered in a previous post, talks about a worldview readers of this blog are well versed in: one where getting started early and with great focus is the key to developing expertise. It’s understandable, and we see what could be thought of as evidence of it all the time, especially in music, dance, chess, and certain sports.

2. How the Wicked World Was Made

This chapter starts out with an interesting anecdote about IQ tests. Essentially, researchers looking at the scores of WW1 vs WW2 soldiers noticed that, even adjusted for other factors, scores went up across the board. One of my favorite stats quoted: “…if an adult who scored average today were compared to adults a century ago, she would be in the 98th percentile.” The tests had to be continually “restandardized” for this reason, with the benchmark of 100 remaining the average.

The tests used were called Raven’s Progressive Matrices, which are designed to test a person’s ability to synthesize and work with complexity, aka fluid intelligence. The study design is important, because cognitive aptitude is very different from knowledge. And I know you know this, but sometimes they get swapped or combined when we talk about people doing incredible things. The metric to keep an eye on is the ability to take on new challenges. Lots of people can do stuff, and do it decently enough. Especially if they’ve had time and practice. A child could learn to assemble a fairly complicated object—fast fashion depends on it, in fact. But do they understand what each part of the process is? The nature of the process? Or are they doing rote repetition? Were I to be tested at a task, let’s say, attaching a sleeve to a shirt with a sewing machine, against a 5 year old who has attached sleeves to shirts for 6 months, I would get a low score, well below average. I’m not only not good at working with sewing machines, but I’m also going up against someone who has done the task for literally 1/10 of their life while also having very little experience at everything else to distract them. Then they give the two of us a test where we have to drive a lap using a car with a manual transmission. I’m not great at that either, but I know how it goes, the order of operations, lots of experience driving cars, and I’m also much larger than the kid, all of which would contribute to me rating higher than the kid. It’s not the people, the problem is the question the test is asking, and the complete failure to acknowledge the way age and life experiences impact certain tasks. Neither of my fictitious tests offered any insight except how good someone was at the specific skills involved in the experiment!

I bring this up because it’s tempting to see the difficulty we encounter learning to play a stringed instrument and chalk it up to a dearth of talent or being at a later stage of life. Seeing 17 year olds who play as if they could teach Piatagorsky a thing or two pours fuel on this fire: they’ve been at life for such a short period of time, and look what they can do! The thought arises: I’m too old, and I’m probably missing something required to play like that. The first part is wrong, but you’re right about the second, although not in the way one might expect. You didn’t get to commit yourself to your instrument when the demands of your life were, for the most part, simpler. We don’t discuss it much, but there is a real advantage to learning a skill before the world robs us of the freedom to screw around a bit. To enjoy something without it having to be your job or a referendum on your worth as a human. Being afraid to make a mistake is something we are taught, although we all agree that nobody is perfect and mistakes are part of life. So what we do, by not naming this conflict clearly, is make the essence of humanity—our tenderness and fallibility—something to feel really bad about.

Humans are pattern seekers. We do it for every conceivable reason, and in adulthood, avoiding shame and the wasting of time become high priorities. In some real sense, the nasty voice in your head is on your side, trying to prevent undue suffering caused by not recognizing the pattern called stop wasting your time, this can’t possibly be right. Life is full of moments when this instinct is exactly correct, when trying for 30 more seconds or 10 more years is damaging.

Examples:

The car feels weird when you drive it, maybe it’s nothing? Rats, it’s a puncture. I kept driving, and now the wheel is bent.

They hurt as soon as I put them on, but I’ll get used to these shoes. Wow, I need 14 bandages and I hope these blisters don’t get infected.

I know they haven’t answered my last two texts, but that doesn’t mean they’re not into me. I’ll send a few more! *cue Bridget Jones All By Myself scene*

Heck, it’s so good, so here it is.

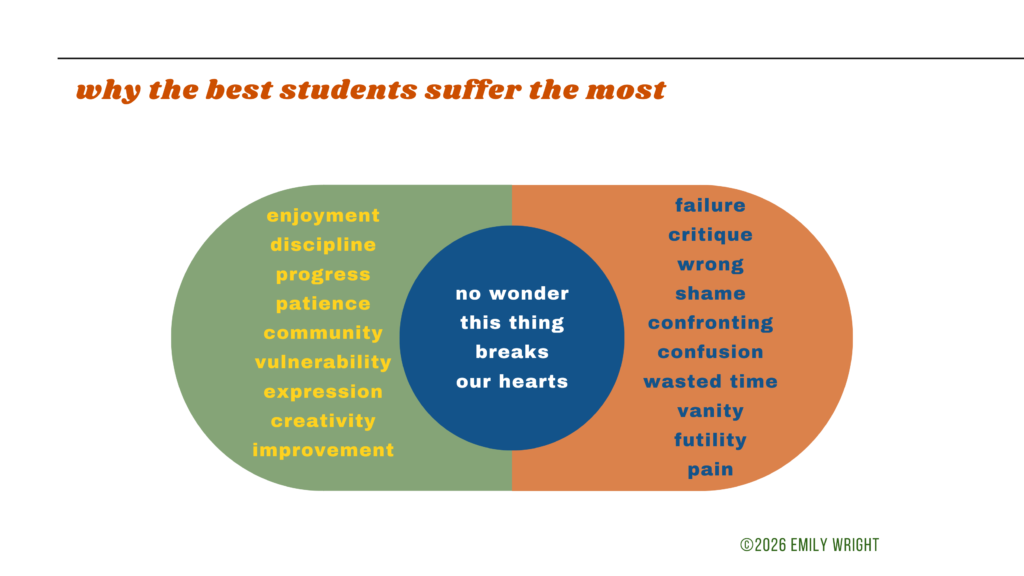

So it’s into this context that we pour our efforts. It’s especially hazardous because the people who find me tend to be wonderfully vulnerable, highly motivated, and serious about music. If you’re doing the right things at the right pace, the process almost immediately starts throwing errors. A schism opens. Squeezing through the cracks to come for the things you love: doubt, dread, and fear.

For every aspect on the left side of that graphic, there is at least one aspect on the right that pulls against it, and if you are a disciplined student who cares deeply about this stuff, it probably affects you more. Here are the correspondences I notice the most:

Enjoyment is susceptible to feelings of wasted time, vanity, and shame.

Discipline, to confrontation, shame, confusion, wasted time, futility, pain.

Patience, to wasted time, futility, and failure.

Community, to shame and critique (uncredited cameo: comparison).

Vulnerability is susceptible to all of it. Every last one.

Expression, to confusion, failure, shame, worries about being wrong, and pain.

Creativity, to failure, futility, fears of wrong choices and critique.

Improvement, oddly, can lead to all of them, too. Because folks like us are awfully good at seeing our progress as an accident or a mirage, so we move the goal posts just to make sure there is never a moment to be where you are on the instrument and appreciate what you’ve done.

We tend to weigh negative experiences as more relevant than positive ones, because that famously kept our ancestors from grabbing a burning log or drinking fetid water more than once. As an exercise, the next time a wave of something big and unwelcome comes over you in relation to your playing (either while practicing or just contemplating), pay attention to where it manifests in your body. Register the amplitude of the sensations. Can you think of an occasion where they would be appropriate? As someone who trends towards anxiety and has had several really scary surgeries, I can name that pretty easily. When my stage fright was at its height, the sensation felt like a heavy, cold glove reaching up through my guts and closing around my throat. I would sweat and vibrate more than shake. My fear before playing a single movement in front of 20 of my peers was identical to the fear I had before my spine surgeries. These were low stress performances. We all had to do a few each semester, and every music major had to attend a few dozen as a requirement. There was an acceptance that these were pieces in transition, that the performance was a first test drive. But my body felt like there was a chance I might not get out of this thing alive.

Tip:

Sometimes feeling your fear in your body (rather than experiencing it as a thinking) helps the freight train of pervasive unhelpful thoughts detach a bit. Your body and mind do not have to feed off of each other like this. Imagine a situation where these feelings are normal and reasonable (a close call with a car/pedestrian, being startled awake by thunder or an earthquake, waiting for a medical diagnosis). Nothing else. Don’t chastise yourself for feeling any particular way, just sort of draw a line from how you’re doing in this moment and know that you’ve felt like this before, and your body wants to tell you about it. As in an art house horror movie, it’s almost always scarier if the monster isn’t named or clearly visible. Being able to label and place the sensations has a way of knocking the fear down a bit.

Many students are already on top of this stuff, which gilds the experience with extra awfulness: If I understand this, if I’ve done the work on myself and my instrument, should this not be…less present? If you’re anything like me, I intellectualize stuff before ever allowing myself to benefit from it. I know this about myself, and while I don’t love the output of it, I do know it comes from something good (introspection and a desire for improvement). Eventually, I’ll have to make the leap and decide that the thing I understand applies to me. Not just everyone else. That takes time, and you are allowed to take it.

Interesting fact: a 2015 study revealed that over 3/4 of Americans land in careers unrelated to their field of study in college. Aside from a lack of high paying humanities jobs, what conclusions can you take away from this? Fluid intelligence sure seems like a useful attribute.

The last thing I’ll talk about is the idea that you don’t know what you don’t know. In Range, Epstein details a series of studies from the 1930s where villagers dwelling in remote areas of what are now Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan were asked to sort objects into different categories. Important to note, these cultures had ways to describe quantities, but they did not have the concept of numbers as abstractions. So, 3 was something that described how many sheep were born. How many bales of hay would sustain the cows. But 5 minus 3 would have been nonsense. They would ask, “5 of…what?” This is not dissimilar to concepts in music. Sure, every student I’ve taught can count to 4 and knows that 4×4 gives you 16. Does that translate to flawless rhythm? Excellent sight reading? You know the answer.

So these villagers were asked to put different colored wool skeins into groups based on similarities. The less remote the village, the better they were at the task. These folks would group shades of red and brown, purple and blue, and white and yellow wool skeins together. Enter the more rural villages, and things change. First off, the words they used to describe the colors were much more specific. The wool was pistachio, not just green. The beige with flecks was cotton in bloom, not just white. When asked to group the items, the premodern villagers refused. “There is nothing in common!” they would say. When pushed, with researchers saying they MUST make some sort of group, they made random choices, and complained heartily about being made to do so. Some seemed to group the wool by color saturation, which I found delightful. These same villages saw no similarities between other examples, too: a square drawn with solid lines was not paired up with the same sized square drawn with dotted lines. The tests have been repeated over time with similarly isolated peoples. In Liberia, young adults with some degree of contact with modernity reproduced the same results, grouping a fireplace, blanket, and a jacket together as “things that keep us warm”, whereas isolated villagers found the entire exercise preposterous. The more remote test subjects repeated the random results when they were forced to group items they could not relate.

Bringing this into a more familiar context, tests of fluid intelligence among western academic students show the same patterns. For questions where no formal training is required to understand what was being asked, students did well. When they opened up the questions to a wide variety of problem solving and groupings, students did abominably outside of their field of study, with English and Biology majors doing particularly poorly. To quote from the text:

“None of the majors, including psychology, understood social science methods. Science students learned the facts of their specific field without understanding how science should work in order to draw true conclusions. […] Business majors performed very poorly across the board, including in economics. Econ majors did the best overall. Economics is a broad field by nature, and econ professors have been shown to apply the reasoning principles they’ve learned to problems outside of their area. Chemists, on the other hand, are extraordinarily bright, but in several studies, struggle to apply scientific reasoning to nonchemistry problems.”

Epstein: Range, p. 46

What I’d like you to contemplate: the reasons why we struggle are not nearly as important as a willingness to engage with the struggle. As you advance, it’s natural to look for familiar methods and principles from other areas of expertise, or even from prior musical work. It’s a useful instinct, and will often reward you with the insight you seek. There are times, however, that you cannot know what you don’t know. Because you’ve lived the life you’ve lived, learning things and gaining skills that would probably baffle your musical heroes. That was not wasted time! What you’ll find as we continue exploring Range, you may even be able to turn it into an advantage.

If this has been thought provoking and you’d like to go deeper, here are a few journal prompts:

Think about what you are most skilled at. When did you first encounter this skill?

Think about a hobby you abandoned. Why did you come to it? Why aren’t you doing it now?

Think about your favorite musician (who plays your instrument) and imagine what it would feel like to play with that kind of facility. How does that differ from the way it feels when you play? What are you doing to close that specific gap?