Maybe some of you remember Devin. He was a very special student of mine who, despite a massive brain injury that resulted in virtually no ability to retain information for more than 2-3 minutes, managed to make major strides on the cello. His caretakers noticed a difference in his retention of other information, too. Something about the lessons was rewiring his brain. Even though he was fairly upbeat in most of our sessions, he would usually close the lesson with the same piece of information: “Am I seeing you again? I really don’t like playing the cello very much.”

At first, I took this with a grain of salt. Brain injuries cause all kinds of interesting emotional issues, from random rage to euphoria. He resented his mother (a violinist) like a teenager, and I thought that this was his way of showing it. But after a while, I came to realize that Devin really didn’t enjoy the cello. Sure, he progressed. Sure, he was improving on other fronts. But he hated it. His injury requires him to live under constant supervision with a team of nurses and his parents making decisions for him. As the weeks went by, I would receive the exact same email from him: “Please tell my mother I don’t want to play the cello any more.” She died a few months into our tutelage, but he kept taking lessons at the request of his father, who was always so warm and kind to me. I found it strangely touching that Devin, who had no short term memory, remembered his mother’s death without complication. This was a signal to me: I called up his dad, and told him that Devin was an adult who, while maybe not capable of holding a job or drawing logical conclusions about the world around him, was very capable of determining what he did and did not like. I heard his dad sigh, but he agreed. Life was, after all, meant to be enjoyed.

I sent Devin an email telling him that we would no longer continue cello lessons, as per his request.

I got one back saying simply, “I’m sorry, but you must have the wrong address. I don’t play the cello.”

There was some interesting banter on Twitter this week. As a teacher, I find much of it very informational, because it’s my job to strike a balance between pushing a student to the very limits of their capabilities without burning a hole in their soul from the necessary discipline, devotion, frustration and grit. The cello is abrasive: I should not have to be.* Part of the Twitter conversation involved the sense that practice became attached to someone else’s approval. In my view, it is a complicated and very emotionally charged issue, which is why I love teaching adults so much. That richness requires me to be inventive and sensitive, but it also allows me to appeal to logic and explanation, which children are not as open to. In striking the balance between cheerleading and drill sergeanting, what I find is that words matter and so does the manner of delivering those words.

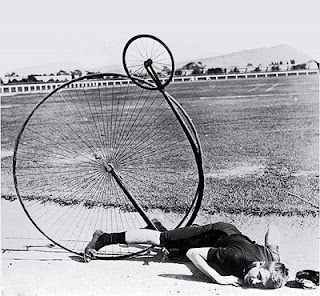

I got a lot of positive feedback about the whole “Yay, Crap!” thing. Every musician sounds like crap at some point during practice, if they’re doing it right. I’m willing to bet even Hilary Hahn and Yo-Yo Ma experiment with new music, new fingerings, alternate techniques, and on the way to their stunning results, falter here and there. Certainly when I’m reworking my orchestral excerpts, I feel Beethoven looking down (and Strauss looking up…hee hee) at me wondering what on earth my intentions are. I am able to persist because of what I call cheerful relentlessness. I do my best, and when I fall on my face, I am at liberty to say, “Holy moly, that was crap!” And then go at it 100 more times. I am also like this with my students, in the hopes of acclimating them to the infinite variety of horrible sounds that are possible as you attempt to play whatever is thwarting you this week. The point is to get through those 100 reps, with absolute focus on technique. It’s a fine line between investment and self-flagellation.

So too, is the line between a teacher observing/assessing and reacting/blackening a student’s mood. I am paid to be a tour guide, a cheerleader, a bit of proof that, despite much jackassery, it is possible for nearly anyone to get pretty dang good at the cello. This last point is perhaps the most important. When a well-meaning student is in the thick of it and making no perceivable progress, it is key to relate their predicament to your own experience. “I went through something similar with Elgar.” “I was stuck in the doldrums on Lalo, too.” “I still have no idea how to play that part really well. Let’s practice this together and figure it out.” Otherwise, the cello becomes something it’s not. Like an impossibility. Like a reminder that you’re an idiot. Like a waste of time. Like something that gathers dust in the closet as a silent, expensive, crowning reminder of everything else you’ve failed at in your life.

Bleh. I’ve been there, baby.

Music seems to be so end-result driven. We buy recordings. We go see performances. Even lessons seem like ends in themselves. What I see is more like a snapshot. Each performance, lesson, or recording is just where someone is at that particular point in time, and then back into the process they go, which is always simmering away somewhere behind a closed door with furrowed brow.

If you’re no longer enjoying the end result, get back into the process. If you’re no longer enjoying the process, change things up. You always have the option to step away from the cello, that’s true. You’ve earned the right to decide what makes you happy. But with few exceptions (and Devin was one of them), I would bet my bow that sticking with the process could bring you happiness yet. It just might not look like you expected it to, and that’s part of the challenge.

When you are weary, find your cheerful relentlessness.

* Although sometimes a student needs a good old-fashioned ass whooping. This results in either a final lesson or a new era. I don’t enjoy it, but it happens about 2 or 3 times a year, and it exhausts me.

Photo from Mastercycling.

4 Responses

Cheerful relentlessness has just become my new slogan!

There's a lot to think about in this post. Thank you.

I think it depends on how you say, "Yay! Crap!" Some people are really sensitive and could be discouraged. Me, on the other hand, I am sensitive, but I tend to be the first to say, "that sounded like crap." I never thought of sounding like crap as a good thing though.

SO: You misunderstand my take on this. Sounding like crap is awful, but it is a part of the process, so why hate YOURSELF for it? Hate the sound, embrace the process, keep working on it and then the sound will follow.

That's the spirit of cheerful relentlessness. It's not that we want to settle for a terrible sound: just the opposite. But in order to get there, we have to persist through some gnarly stuff. Taking that stuff and accepting it as part of the experience and reducing its negative impact allows us to continue when it would be very easy indeed to abandon our practice in favor of more positive things.

Persist! We all sound bad sometimes!

So So So True although it took me years to realize that bad sounds were just a part of playing a string instrument. The ability to make all kinds of sounds on the cello is a one of the reasons I love it. It can be as expressive as you want. This flexibility comes with a downside of missing notes and sounding like crap. If you stick with it, you'll sound like crap less often and play what you really mean.

I wouldn't trade that flexibility of sound creation for anything. Yay crap!